Gonna take a stroll into the stone age by way of the Houston Museum of Natural Science. C’mon. Ride along. (“It’ll be fun, he said…”)

Our journey back begins at the top of the stairs. Big fan of stairs. Gotta get exercise. We turn right and start walking backwards through the calendar… past the Hall of the Americas, which is back some 5-700 years or more, past the Maya, past the Aztec, past the Inca (all of which are normally good for a stop, but today we have deeper destinations in mind), past the new old Egyptians (few thousand years here, we’ll have to check these guys soon)… we’re crossing centuries with each step now… and here we are, 17 or maybe 20 thousand years ago, back to the Paleolithic, looking for limestone caves lit by flickering grease lamps…

The first part of the exhibit (This IS a museum, not an actual time portal. Nothing’s perfect.) is standard “historical era” museum exhibit – displays of old photographs, enlarged, with extended captions with basic information about the history of what we’ll be seeing. I read them all quickly, getting some background about the discovery of Lascaux, making photographs instead of writing notes, and carry on past the entryway.

On the left, here, a display explains the negative effects of human visitors on the cave ecosystem – increased water vapor, carbon dioxide, heat – and some sort of gee-whiz metering system displays, on an odd 3-axis readout, how much of each the individual visitor creates. The display does change as I step up to the metering point, but as I’ve no idea how to interpret the screen, it’s of limited interest. No matter, I’ve spent enough time around cavers to be aware that human explorers and tourists aren’t really good for caves. Onward.

Staying against the left wall, we come to a small room with a 3D video loop running, and a basket of glasses. They’re an awkward fit, at best, over my own, but good enough. Graphics show the “virtual Lascaux” – showing virtual artists working on virtual art in the virtual cave, showing also some of the walls (from the inside AND outside, as though the walls of the cave were transparent) so we can see what’s where in the cave. It’s a fantastic bit of work, complete with 3D bats zooming out of the screen. Cute.

The video lasts only a few minutes, then we’re back to the main room to check out the main part of the room display, a scale model of the cave complex. These are fiberglass molds, plain white, mounted on plywood-covered stands showing the relative size and location of rooms with art.

One room, the Hall of the Bulls, also includes a human figure for scale.

Each also includes a caption label and a monochrome rendering of the art found in the room. I found it much more useful than the virtual cave for developing a mental picture of the entire site, though I would have preferred to have the rooms connected. Being able to see into the rooms was, I think, less significant than having the entire complex appear as a single model. It’s still very helpful.

Against the far wall is a well-photographed display explaining the construction of “Lascaux II,” a replica of the original cave built by the French a few hundred meters away when it became apparent that the original cave couldn’t sustain significant visitor traffic without permanent damage. It’s titled “Seeing without damaging” – fitting, since that’s the entire point here.

Another exhibit, just in the corner, describes the artistic process involved in the creation of Lascaux I and II, with samples.

There’s also another “gee whiz” machine – a laser scanner which creates a 3-dimensional rendering of a small mockup of a wall section at the press of a button. (In theory, at least.) It’s slightly interesting except that I couldn’t see how the contours of the rendering matched the actual mockup right in front of me. The theory’s sound, though, so again, no matter.

A small dark hallway leads off here; as an old cave-gamer I can’t help but follow it. (But it wasn’t a twisty little passage, no fear.) There are exhibits here of artifacts (and replicas of artifacts) found and gathered in the early days of the cave, where proper archaeological protocols were frequently overridden by the need to salvage something from the flood of visitors. Tools, bone fragments, painting and engraving gear… all gathered in a hurry without proper records. It’s always a problem when archaeological sites become objects of public interest before they can be properly conserved.

Another display explains the process of recording and duplicating the artwork by various means and the work that was done in the early days. Available dark photography, redefined.

Back through the hallway to the model, and now there’s only one passage left: The Cave.

(deep breath)

WOW. Just WOW.

It’s dark in here, except for the low lights on the cave walls and comparatively brighter spots on the four human figures. Immediately to my left, on a panel from the Hall of the Bulls, a small herd of bulls splits, moving left and right. It doesn’t take much imagination to hear their breathing and the stamp of hooves and… wait, did that last bull just toss his head? Perhaps? But no, that’s just the light and shadow playing with my head. (Not too hard to do here.)

Just past the first panel, a young woman (who could make a good living as a model) in what appears to be a reindeer-hide onesie (with the fur in) and a beautiful beaded headpiece is pointing across the cave, apparently talking with an older man who sits beside her with a spear in his hand. I can’t help but notice that the old hunter resembles a prehistoric Liam Neeson – perhaps his next starring vehicle? He’s getting on up there now….

Beside them is the Black Cow in all its glory; if I’m careful I can just fit the cave denizens and the black cow panel into a frame, and with a little balancing work on the lighting (very glad for digital camera here…) I can get the whole thing.

As I turn around so I can grab a rail and stand up, a herd of stags files by behind me in spooky silence.

Beyond the stags, a model of a woman draped in a fur robe and beads paints designs on the face of a small child.

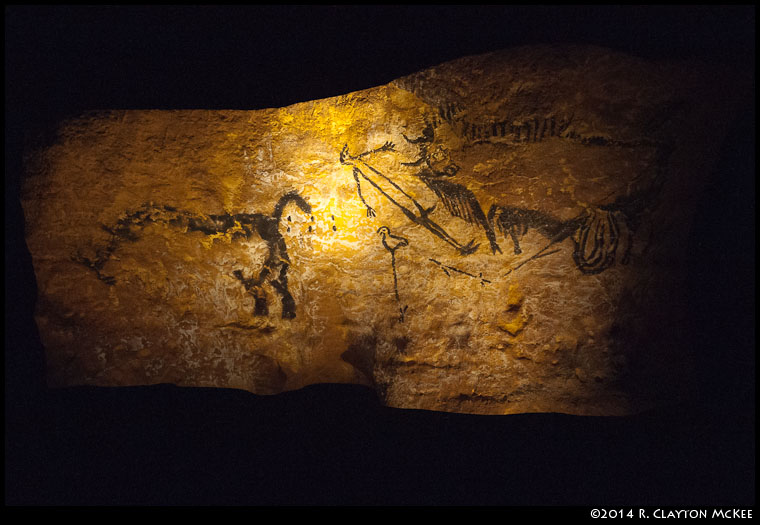

Beyond them again is the endpiece of the replica, the shaft scene.

This is the only human figure in Lascaux; with him are a bird, (Officially it’s a bird on a stick but I want to say it’s a bird with very long legs, the right one not actually attached to the body.) a speared bull or bison, and what I’m told is a rhinoceros at left. (I have a hard time seeing a rhinoceros in France, ice age or no ice age.) The man, the bird, and the rhino are unique to this scene. This panel is an odd duck; it doesn’t feel like a match with the rest of the paintings, and the rhino is painted in a different technique. There’s speculation that a different artist did this scene, possibly coming in to the cave from a different entrance that hasn’t been found yet (and which may not exist any longer.)

Across the exit is one last panel, The Crossed Bison, which is interesting in that it appears to me that the proper viewpoint can be had only by sitting on the floor looking up. Oh well, anything to get the shot.

It’s good for me that this is the end of the cave replica, because by now my eyes and visual sense are so thoroughly overwhelmed that I’m needing to sit somewhere for a few minutes just to decompress. I walk over to check out another video theatre and perch on a stool. The video is all about the artistic and symbolic approach to the Black Cow. (that would be this guy, again:)

I’m sure the film is magnificently done, but I’m not really in condition to remember most of it, and the only part of my notes that I can make sense of says “The Black Cow was necessarily a cooperative effort. Several people would likely be needed to do all the tasks involved in putting it there. The amount of time and effort needed makes it probable that this was an image of great symbolic meaning.” The artist would have been perched on a small ledge several feet above the floor. There would have been someone else, probably, mixing his paint, filling and moving the lamps, and possibly helping hold the artist on the ledge. There’s more about the “shield” or geometric pattern at the base of the figure; it’s thought to be perhaps a caption of some sort or possibly the artists’ signature symbol. As with most such things, many questions, few answers.

In the center of this second room is a stand of displays relating to the artistic techniques – the use of moving lights (flickering grease lamps) to suggest animation (and for an example of the theory, there’s an honest-to-goodness zoetrope wheel!), a discussion of the possibility that the stags are swimming since only their heads are visible … but, the question remains, was this meant to be five stags swimming a river, or one stag swimming five times? We don’t know.

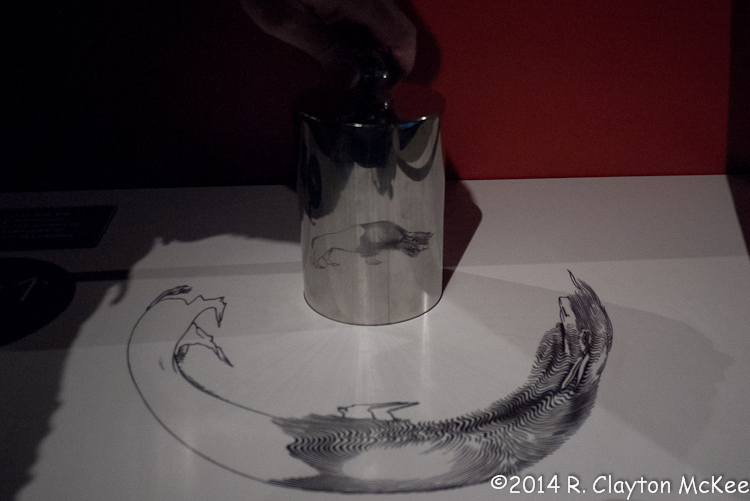

The most interesting part of this little kiosk is a discussion of anamorphic perspective – paintings crafted to be seen from a different point of view than that of the artist. Several of the bulls and bison are high on the walls, but are distorted slightly so that they’ll appear correct from the view of a person standing on the floor of the cave. There’s a helpful drawing of a bison next to the discussion, complete with a distorted mirror to make it look more or less right…

Fortunately I have artists in the immediate family, and perspective distortion is part of the technique of photography, so it’s easier to understand from a technical viewpoint, but this is high-level artistry, folks. Perspective disappeared from two-dimensional art at some point after this and if memory serves didn’t reappear until sometime in the early Renaissance…

Off in a corner is much of the standard paleo-anthropology “life and times in the paleolithic” exhibit with some pretty examples of spear points, lamps, and flintwork, and a large display pointing up that Cro-Magnon were modern humans, very much like us. Same brainpower, same intelligence, same physical structure. Put them in modern clothes and they could move in next door.

And on the last wall is one more large part of the exhibit – and the only major disappointment. It’s a wall of monitors showing clips of various significant personages in the modern history of Lascaux, with recorded comments from each. But the original recordings were in French and the English overdubs were done at a low volume compared to the original playback, so they’re very hard to hear and understand. One, a philosopher musing about something, was set at such a low volume that it was completely inaudible. As he was probably considering the meanings of the art, it was probably quite interesting, if I could have heard it. The second main issue was that the speakers were filmed looking around, but not speaking. Listening to their voices while their mouths weren’t moving was a somewhat surreal experience. We’re not used to that. I wound up ignoring the monitors and just trying to make enough sense of what was said to take notes. Most of the comments repeated or reinforced things already mentioned in the exhibit; the summary would be “This is magnificent and important, but we don’t know that much about it.”

Which means I’m in good company.

There will be more later; this is a preliminary part of a larger Rock Art story for my somewhat more serious blogzine, The Other Texas. I’ll post a link here when it’s ready but there’s a significant amount of research, learning, and field reporting to be done first. I just wanted to write up my impressions and notes on the Lascaux exhibit before I lost them.. And after writing this it seems kind of a shame not to post it. Thanks for riding along to the end here, and I hope it was a tenth as interesting for you as it was for me.

”Scenes from the Stone Age: The Cave Paintings of Lascaux” will be at HMNS for another week or so if you feel so inclined. Tickets for members are $12; for non-members they’re $25.

(I have to throw in a totally unpaid plug for museum membership, here, too. Been a member for several years now and in a city with a significant number of major museums this is one of the jewels. Support as many as you can, of course, but if you can only afford one this would be it.)