It’s important to remember that while we (the Good Guys) were sticking tin cans on top of missiles, and stuffing brave young men into those tin cans, and launching them out into the big fat middle of nowhere, we were NOT alone. The Soviet Union (also known as the Evil Commie Bastards) was attaching little hollow balls to the top of their big heavy rockets and stuffing some of THEIR brave young men into those little hollow balls, and launching them out into the big fat middle of nowhere TOO.

And, in fact, that was a big part of our reason for doing it… because when the Evil Commie Bastards put Sputnik into orbit while we were still fiddling around with Cold War missile systems, it occurred to the brightest minds here, as it doubtless did to the brightest minds THERE, that where there was a beeping little satellite there could almost as easily be a bleeping big BOMB, and our geniuses and political leaders (the distinction matters) decided that if there was the possibility of death and destruction being rained down from on high, it should absolutely be US doing the raining down, since being the rained ON was not going to be particularly popular.

So we went full-bore into the “To The Moon!” effort… and having proven that we could blast men into orbit and bring them back home still functional, the next step involved building vessels capable of controlled flight. See, though most of us didn’t really realize this, the Mercury capsules were mostly ballistic. The astronauts had some attitude and pitch controls, but orbital trajectory was largely fixed at launch. Getting to the moon would require much more sophisticated equipment.

Thus Mercury Mk II (better known as Gemini.)

The focus was on building systems that could actually serve as working platforms, rather than simply experimental curiosities. Immediate goals were maneuverability, rendezvous and docking capabilities, better life-support, power supply, and long-term living arrangements. (There were conceptual plans for Mercury and Gemini-based orbital stations, though nothing ever seems to have come of them…)

And, of course… spacewalks. Which meant spacesuits.

There are a couple of panels in the Astronaut Gallery at Space Center dedicated to the rocket science involved in space suit building, because they’re essentially unpowered mini-ships and quite complicated to design and build. Rocket Science really IS more complex than most of us tend to think.

This is an exhibit suit described as “identical to the one Ed White wore when he performed the first U.S. Spacewalk.” It had to provide thermal protection, a pressurized atmosphere, maneuverability, and protection from micrometeorites… turns out space vacuum comes complete with lots and lots of itty-bitty flying rocks zipping around at a good clip. So the engineers came up with this version, which is basically an upgrade to the standard Gemini suit. It’s 10 lbs heavier (it weighs 34 lbs) and 22 layers thick PLUS a heavy felt layer for rock padding. The waist pack provides attachment points for the tether and umbilical package which kept White breathing and tied to the Gemini capsule while he was floating around. They put an emergency oxygen supply in the chest pack, just in case something went wrong.

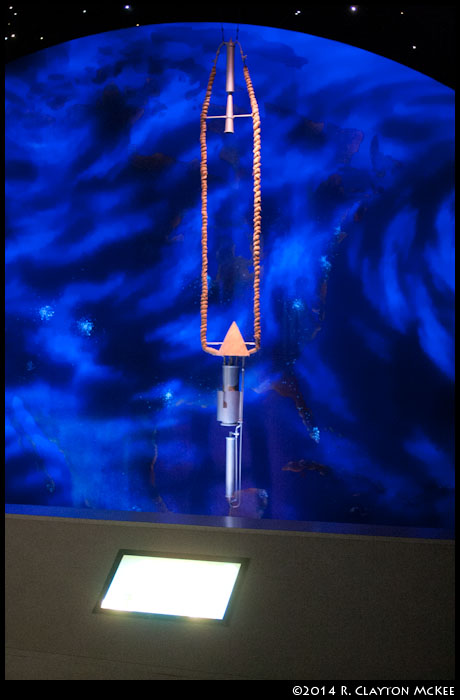

For maneuverability, he had this gadget

which is basically a handheld spray jet with two nozzles about a foot or so apart (you can’t really see the one in back, but it’s there…) and a modified 35mm Nikon F camera on top. (As a strong proponent of “never go out without a camera because you just never know,” I heartily approve. Even if it IS a Nikon.)

And, over in the museum is White’s actual Gemini IV capsule hanging from the ceiling with another of the training suits used before the mission.

I love museum exhibits like this. To me, they give a better feel for what it might have felt like to do the “floating among the stars” thing. White floated in space for about 20 minutes, during which he also set some sort of record for the fastest coast-to-coast flight in history. While he was floating around (and what a trip that had to have been….) he told the pilot, James McDivitt, “I’m not coming in… this is fun.”

At the end of the programmed walk, when he was scheduled to climb back into the capsule, he radioed back to Mission Control (in Houston, for the first time) that it was “the saddest moment of my life.”

But he DID crawl back inside, came back to Earth, and finished the mission.

Which means I DO get to learn (and write) more of this.

******

Incidental note: I’m a member of a facebook group – “You Know You’re a Writer When…” and my latest contribution was “You know you’re a writer when you do crazy stuff just so you can write about what it’s like to do crazy stuff.” That much is autobiography.

Last time I was down at NASA I did the crazy stuff. Got into a spinning chair and let the guy turn my inner ears inside out, (surprisingly not too unpleasant until I tried to stand up afterwards and the floor just would not cooperate). Took a fast bouncy walk in 38% gravity (not too bad this time but I really like my feet to stay where I put them). Actually climbed to the top of a 9-meter (that’s a little less than 30 feet for you Old School USians…) scaffold, let somebody hook me to a cable that was supposed to reduce my “felt weight” to roughly 80 lbs, and yes, in a moment of total batshit insanity, actually jumped off the top of the tower. Honestly that was probably not the single craziest thing I’ve ever done, but at that particular moment my subconscious was really not interested in comparison shopping.

It was an interesting experience. I think.

The part of my brain that analyses and discusses these things is still mad as hell at me for shoving him into a closet long enough for me to tell my legs “Jump. NOW.”. He’s not really speaking to me at the moment. (Either that or he was just so freaked that I actually DID it that he really missed the event.)

The half-a-second of freefall before the cable caught me was simply wordless – not really long enough to have any emotional context at all, except to observe that a big part of my subconscious does NOT like freefall even a little bit. Then the cable caught, the winch screamed, and I kept falling just about as fast as before (None of this “float down like a ball of thistle” stuff for ME). About that time, the ground person looked up and said “bend your knees!” I did, and about that time my feet hit the ground and stopped falling. Unfortunately the REST of me kept on falling for another couple of seconds. When your feet stop and the rest of you doesn’t, it’s awkward. It left me half-sprawled on my butt at the bottom of the tower. I assured the ground crew folks that I was okay, then climbed right back up (Easier than you might think when you weigh a third of normal) with nothing broken but my dignity, and carried on.

I’m still not sure how I feel about having done this, but I have a new buff and polish job on my “crazy writer” credentials.

For whatever that’s worth.